Why you need more "Inefficient Curiosity" to create anything truly great

And why the value of curiosity might only make sense in a few years time

The efficiency allure

If you’re a type A personality, you’re probably used to making progress. In fact you may love nothing more than ticking off a list, getting things done, making strides towards your goals. You might wring your hands over long meetings, inefficient processes, or distractions. You might take the shortest route to work, check your KPIs first thing, and make sure you are always getting things done.

Most of the time, at least if you’re motivated by making an impact on this earth, this is a pretty good strategy. You can’t really create anything novel in this life without a lot of hard work, and you’ll need focus and structure to know where to channel this hard work, and to avoid wasted cognitive energy starting thing from scratch.

Plus, if you focus on efficiency and productivity, by most standard measurements you’ll also be doing well. You’ll probably earn good money, and help put some things out in the world. But will you create something truly interesting?

If you want to create new things, you need to do what hasn’t been done before. This involves inefficiency. As much as you might like to - in order to assuage your productivity guilt - you can’t really optimise this process. I call this state “inefficient curiosity”. Real curiosity - the kind that creates first principle thinking - is often unplanned and unoptimised. It has no real goal. But history tells us that this seemingly dumb and inefficient curiosity, time spent that is hard to justify or explain, is actually the secret behind creating some of the most unique inventions of our time.

Efficiency = doing what has been done before

If you were programming an AI that needed to produce the next technological invention that would change the world, you probably wouldn’t program it to study calligraphy. You’d also be unlikely to tell the AI to take a year off and travel, or take a week off to read completely unrelated things. But that’s exactly what Steve Jobs, Sam Altman and Bill Gates - some of the best innovators of our time - credit to their success.

One reason that doing weird unproductive things can ultimately end up so “productive” is that if we optimise ourselves for efficiency only, it is inherently past-based. We can only really optimise ourselves or be efficient if the parameters are already “known”, if we are doing what has been done before.

So when we laude the idea of efficiency or productivity, we are really praising the idea of “doing more of what has been done before, but quicker”. This is great when we’re doing repeatable tasks like doing our taxes, cleaning the house or having a painful operation - no-one wants an inefficient surgeon - but productivity or efficiency will rarely produce anything new.

The dangers of ‘early optimisation’

The thing that puts people off following their curiosity without any plan is that it can also take many years to suddenly appear relevant. It can be hard to justify. While Jobs, Altman and hundreds of the other best innovators out there have followed their curiosity for curiosity’s sake, and done things that make no real sense at the time - many other people crumble under the pressure of needing a five year plan, optimising their life so much that they miss out on experiencing things that could have a big impact on the world, eventually.

When I interviewed Kevin Kelly the first time for the Out of Hours podcast, he told me he thinks people should be working on things that ‘don’t have a name yet’. Kevin is the founding editor of Wired Magazine, a New York Times bestselling author and all round ‘most interesting person in the world’ (at least according to Tim Ferris). Things that don’t have a name yet are some of the most innovative, he reasons, and they also pay dividends. “The greatest rewards”, he claims, “come from working on something that nobody has a name for”. Kelly warns people off optimising their careers too early, as once you have optimised you have shut down serendipity. But a lot of people early optimise precisely because working on things that ‘don’t have a name yet’ are not socially approved, they have no pre-existing social capital. These things can be laughed at by future employers, investors, or feel embarrassing due to their lack of recognisable meaning or social credibility. Or - pursuing these things can be seen as a waste of time when you could be climbing a ladder that already exists.

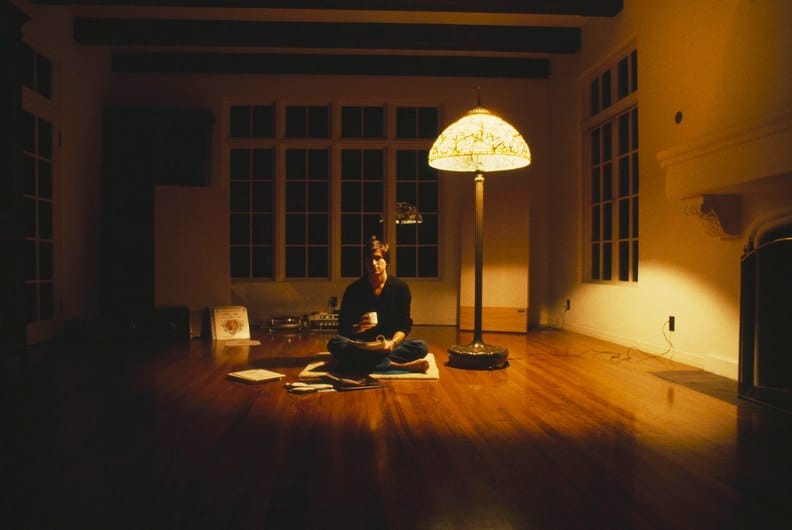

Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs - one the greatest innovators of all time - refused to early optimise. He famously shares in his Stanford Commencement Speech how he quit University, and it was only once he'd quit that he could join the classes that genuinely interested him: which included calligraphy, learning about serif and san serif and what makes typography great. He speaks of these calligraphy classes, saying:

"None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. Much of what I stumbled into, as I followed my curiosity and intuition, turned out to be priceless later on”

Jobs wasn’t from a wealthy family, and dropping out of college wasn’t something he did lightly. In fact, Steve Jobs’ biological mother had almost refused to sign the adoption papers when she found out that his new adoptive parents hadn’t graduated high school or college, and she had only relented when the adoptive parents promised that Steve would go to college. By dropping out of college and instead pursuing a random interest, Jobs did something that didn’t seem smart at the time, that had no “practical application” in his life, and that no doubt upset his adoptive parents.

He also travelled. He set out across India, and also was hugely influenced by Zen Buddhism. “There was always this spiritual side,” said Mike Slade, a marketing executive who worked with Steve later in his career, “which really didn’t seem to fit with anything else he was doing.” Except, this spiritual side did fit what he was doing. It just wasn’t immediately obvious.

Jobs had no immediate plan to use these calligraphy, or his zen buddhism interests in his day-to-day work. It wasn’t optimised or part of a bigger plan. But years later, he ended up producing the first Macintosh computer, followed by the culture-defining iPhone, where the minimalist design - born from a love of design and zen simplicity - was one of the key differentiating factors. He didn’t take these classes knowing that, he was just indulging in “Inefficient Curiosity” that ended up paying dividends.

Sam Altman

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, had a similar period of unoptimised curiosity. After the sale of his first company, he took a year off to travel and explore with no real goal. In an interview he says:

"Taking a year off… It was one of the two or three best career things I ever did. In that year I read many dozens of textbooks, I learned about fields I was interested in... I didn't have any idea they were all going to come together in the way that they did but I read about Nuclear engineering... AI... Synthetic biology... investing... I travelled around a lot...

I started doing all this random stuff, and out of all of it, almost all of it didn't work out, but the seeds were planted for things that worked in deep ways later”

Sam Altman has since become CEO of OpenAI - the company that brought us ChatGPT, AI’s “iPhone moment”. He’s also invested in hundreds of companies including Oklo - a nuclear company that recently listed on the stock exchange. Once again, idle curiosity in areas like AI and Nuclear ended up paying dividends and ‘making sense’ further down the line.

Non Linear Creativity

Brilliant things requiring unlinear paths is true for creative fields too. George Lucas could have sat down and optimised what would make most sense for the market, like many of the more forgettable Netflix films do today, but instead he brought in new never-seen-before influences, that he’d seen in Japanese film culture, into Star Wars.

At film school he was exposed to Akira Kurosawa, a Japanese director. “I was completely hooked”- he says - and he watched as many of his films as possible. It was in 1977 when he made the first Star Wars film - and even though he’d learnt about Japanese film ten years prior - he brought in these influences, like Samurai history and the iconography of the feudal Edo period, into Star Wars. It is this irrational passion, the getting ‘completely hooked’ many years before when it was immediately relevant, that creates the fertile ground for new multi-disciplinary inventions to be born. If he was obsessed with real-time efficient output he may have never indulged in the input he eventually needed.

Inefficient curiosity is needed more than ever

The modern world has a love of efficiency because it allows for control and measurability in an overwhelming and uncertain world. Efficiency also allows us to drive down costs through repetition and scale, and it allows us to create structures that don’t depend on the uniqueness of the individual. But any person or organisation that wants creativity and innovation, or wants to create something truly novel, should be wary of efficiency as the only goal. In a world where the repeatable is increasingly performed by AI, we need creativity and uniqueness more than ever. And as we have seen, efficiency relies on what has been before, and it also struggles to embrace moments of slack time that are so essential for truly unique and defensible ideas to cultivate. So the next time you find yourself strangely interested in something like textbooks, calligraphy, or Japanese culture - invite yourself to spend some time there. Moments of “inefficient curiosity” might just create the most interesting thing to happen to your business - resulting in investments that other people don’t see, creating films that other people won’t make, or building a product that will go on to change the world.